In the eighth century AD, Japanese potters learned the method of glazing using lead salts from China, marking the beginning of glazed pottery production in Japan. Ash glazing was also practised, which melts at temperatures above 1250 ° C. At this point it seemed that glazed ceramic was going to blossom: instead, only the Seto kilns maintained the ash glazing technique, transmitting it to the subsequent Kamakura Period (1185-1392).

In the Momoyama period (1573-1603) Japanese ceramics underwent considerable development: new kilns spread to Kyūshū, Karatsu, Agano, Takatori and Satsuma, while in the Kyōto and Imari regions the tea ceremony (chanoyu), stimulated the creativity of the existing production centres. Two military expeditions to Korea in 1592 and 1597 gave Japanese military leaders the opportunity to bring many Korean potters to Japan, custodians of superior technical and artistic skills.

In the Edo Period (1603-1867) the production of ceramics was mainly concentrated in Kyōto and Imari in the province of Saga. The kilns established in the fiefdoms (han'yō) were genuine commercial enterprises administered and controlled by the military chiefs: in fact, they constituted manufacturing centres which were important for the economy of the fiefdoms, producing and distributing not only common and everyday crockery for “mass” consumption, but also works of art, used as official and diplomatic gifts.

Porcelain was a precious imported product from China and Korea, impossible to reproduce or imitate, which had been known and admired in Japan for several centuries. This situation was revolutionised when in 1617 clay suitable for making porcelain was discovered in Izumiyama in the territory of Hizen, in the north of Kyūshū near Arita. Initially, porcelain called sometsuke was manufactured, summarily decorated in cobalt blue under the glaze like Chinese prototypes, establishing a lasting model for Japanese everyday pottery. Soon after, Japanese production greatly gained from two historical circumstances: the ever-growing demand for porcelain from European customers and the political crisis of the Chinese Ming Empire, which led first to a slowdown in exports and then, around 1660, to the decline in Chinese production destined for the West. Japan benefited from these events, replacing Chinese tableware with the same or similar products.

The European clientele, through the Dutch East India Company, sent pottery shapes and outlines to Japan, as well as precise indications on colours, designs and ornamental themes.

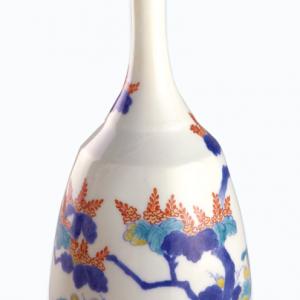

The name Imari refers to export items, typically decorated in blue under the glaze, red and gold above. Imari is in fact a port located near Arita, the largest ceramic production centre, from which the porcelain began the long journey to the West. The Kakiemon style, started around 1643 was highly appreciated in Europe until the mid-18th century, distinguished by the vivid palette of greens, yellows and shades of blues, along with a persimmon orange-red colour enamel, which stands out.

Some fief kilns, such as Kutani, were short-lived; others, such as Nabeshima, remained active even if only to meet the “representational” needs of the military aristocracy; still others, such as Hirado, Satsuma, Seto and Kyōto, successfully competed on the international market during the mid-nineteenth century, exerting significant influence on the end of the century Art Nouveau movements.